|

If you are reading this page, it is because you just heard the word “manga” for the first time. It is a strange and foreign word that confuses and intrigues you. You want to know what it is and what the big deal about it is. … On the other hand, if you already know what the word means, than the following will just be a waste of your time and you should click that nice shiny “back” button on your internet browser’s toolbar right this instant. This serves simply to enlighten the ignorant and not much else.

Now then, let’s define this first: “Manga” is just a Japanese Comic Book. It’s as simple as that. Here is the key difference between them: Comic Books (like the German Club Nintendo Comics, just for example) are read left to right. Manga on the other hand is read right to left! That said, just about every scan we have that came from Japan will need to be read backwards in a way.

You see, books existed in Japan for just as long as books existed in Europe (give or take a century). However, since both areas of the world were isolated from each other by land and sea at the time, there was never really a clear decision to say “all books should be read the same way!” since they were too far apart to even send a simple telegram for making a common agreement – it just didn’t exist.

If you can’t understand that, then take this example: North American appliances don’t work in Europe because the electrical plugs/outlets there are designed differently. Manga vs. Comic Books is more or less the exact same as that.

I know the sometimes rather smart Generic Kirby Fan 17625623 (also known as GKF*smashheadonnumpad*) will suggest; “How is that a problem? Why can’t you just horizontally flip all the scans in MS Paint or something so they can be read normally?” |  |

For a while, we’ve actually considered it. That is a practice that has officially (and obviously) been defined as “flopping”. Sure, it fixes that problem, but there are a few things about that flesh out more problems.

- Sometimes the original authors simply won’t approve any modification of their finished works, for it’s a sign of disrespect. (This is a mild case of it though, with more extreme example of modifications being sorts of censorship.)

- Other times, it leads to misunderstandings within the pictures itself. For example when a Buddhist Swastika is flipped, it begins to look like the Nazi Emblem. In other cases, text like Road signs or on T-Shirts are flipped, it will mix up the word (A character wears a shirt that has “MAY” written on it, but when flipped the same shirt reads “YAM” instead).

- The text and the image will begin clashing. One of the most known times when this has happened was in the English Manga of InuYasha, when the text said that Miroku’s right hand contained the Wind Tunnel, when the pictures showed it in his left hand instead.

That said, the reason we don’t flop is not only to keep close to the original, but to avoid any unwanted misunderstandings. Besides, flopping is a bit outdated as a practice. Most newly published Manga in English retain the right-to-left reading patterns, and even use it as a selling point.

|

|

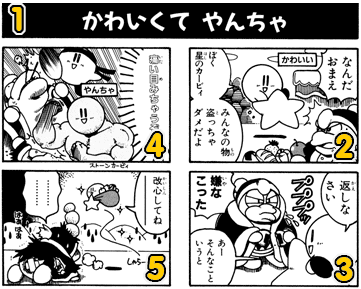

Reading 4koma

4koma Manga (or yonkoma) are no different from basic comic strips found in the newspapers. As the name states, they are four panels long each. They flow in the order of from top-to-bottom with the title in the black box being the first. The usual exception to that rule is when they are on cover pages with the title image on the top. In that case:

Next comes the speech bubbles inside the panels. This is where the right-to-left rule really comes into play. Start with anything in the top-right corner of the panel, then move to the top-left, then bottom-right, then bottom-left.

*Captions are usually found in little boxes. They can be read at any time at all, though you would prefer to read them before the speech bubbles.

- Related Notes

- You might occasionally see a ※ symbol (an X with a dot in each crevice) near the bottom or side of the page. This is a Reference Mark.

- In Japanese it is used to introduce comments and remarks. Unlike asterisks (*) it is not used to link an item in the body of the text to a footnote, but to draw the reader's attention to an instruction or precaution or to indicate that some information is subsidiary or parenthetical to the main text. However, due to the widespread use of computers, both the reference mark and asterisk are used interchangeably.

- It said that leaving ※ symbols intact during a Japanese to English translation is never really appropriate due to how it isn’t even an official form of Latin punctuation. … However, we will be leaving them in during our scanlations due to the use they serve, as well as the fact that you guys now know about it. Isn’t that helpful?

- Traditional Japanese, while still following the right-to-left rule, is written vertically. This sometimes makes the speech bubbles in there harder to translate into English due to the fact that normal horizontally written English just won’t fit inside. While we will try avoid it, the English might be written in vertically at times when it just won’t fit in any other way. (Being an exception, Captions are read from left-to-right.)

|

|

Reading Tankobon

Tankobon is when the Manga formatted the same as a visual novel or series comic book. In these, the panels can be found in virtually any sort of layout or shape possible.

This diagram should cover the basics for you.

|

|